Working life | ‘We are still only at the cusp of what might be possible’

Helen Starr is a cultural activist and producer who moved to the UK from Trinidad in the early 1990s. She founded the Mechatronic Library in 2010 to enable museums and artists from marginalised backgrounds to create artwork using new-media technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality, game engines and 3D printing. Her work explores racism, genocide and how European people came to see themselves as gatekeepers to the personhood of others.

What does your role as a world-building curator entail?

Worldbuilding is the process of constructing an imaginary world, sometimes with a fictional universe. Developing a coherent history, geography, and ecology is a key task for worldbuilders. This allows speculative imaginaries around alien social, cultural and economic customs to form.

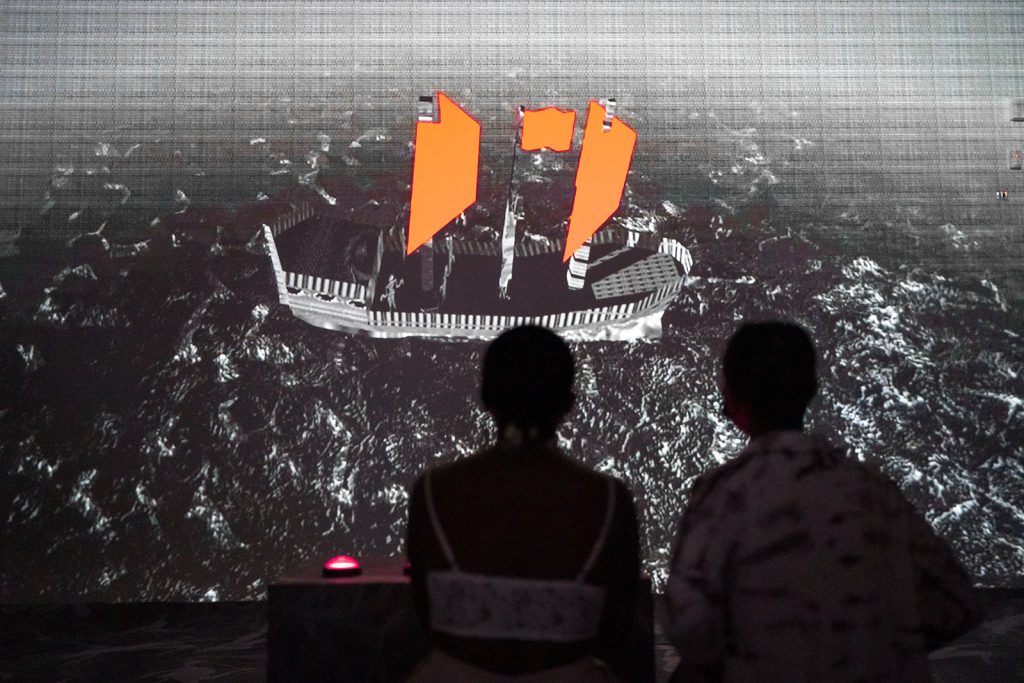

The longstanding proponent of worldbuilding is the artist; be it literature, music, theatre or visual art and the new arrival of AI technologies, we are still only at the cusp of what might be possible in terms of encountering these spectral worlds. At the moment Game Engines and Virtual Reality present the best opportunity just now to immerse yourself in these fantastical experiences. To paraphrase my dear friend and long-time world-building colleague Peter Bonnell, the real trick in any form of world-building is getting the cosmology right.

I would say my role as a world-building curator is to support artists in examining the cosmologies from which their interactive, immersive experiences are built. This is key to moving the work beyond entertainment and into an artistic experience. As this futuristic medium evolves, it will become ever more important for curators to guard the difference between the two equally valid encounters.

How was the Mechatronic Library formed?

Sometime in 2008, deputy Labour leader Harriet Harman defended her decision to wear a stab proof jacket during a police walkabout in Peckham, an area mainly made up of Black African and Caribbean people such as myself. I realised that unless we were able to control our own representation, this deeply ingrained, negative othering would continue unchecked. We needed contemporary works in art galleries and museum collections with counter narratives to the dominant secular, heteronormative, colonial cultural system.

I felt very clearly that if artworks used the most cutting-edge software technologies then our decolonial, othered ideas would be planted into the future. The Mechatronic Library was founded in 2010 to commission artworks which use AI, Interactive and Virtual Reality tools so that othered perspectives could shape a new futuristic cultural agenda for the most pressing social, economic and political issues.

What do you think the future holds for digital as an art form, particularly for marginalised artists?

Digital technology provides some of the most powerful open source tools for the making and disseminating of content. It puts real power in the hands of marginalised artists who are trained to use it well.

Who inspires you?

The brilliant Jamaican philosopher Sylvia Wynter inspires me. Wynter reminds us that other futures are possible through the creation of different value sets. And, the current heternormative, culturally and economically extractive path laid out by humanism is just another form of storytelling. She unpacks why we are conditioned to think there is only one type of civilised and modern way of life, and invites us to think anew towards a more gracious and less exploitative way of being in the world. The artworks I commission seek to tell this very different narrative.

In your work, you ask why marginalised people would engage with temples of power and privilege. What’s your answer?

Well, we all know why marginalised people should. We contribute to civic life through our current and the historic taxes, and these taxes built cultural temples of power and privilege. Marginalised people have every monetary right to claim ownership of these grand structures.

However, do they practise the duty of care that deserves our presence? Or do they replicate the oppressive cultural strategies? In my opinion, these places are often plagued by the lazy binary that marginalised cultures and histories can only be presented as wretched or assimilated.

Contrary to Western belief, our own philosophies and belief systems challenge and unsettle what Sylvia Wynter refers to as the "overrepresentation of European man". And this Western blueprint of an extractive capitalistic system needs to be redrawn to survive a climate-changed future. Maybe if these stale, male and pale temples embraced other ways of being, we would enter them. Otherwise, why would we?