Art speaks louder than words

Earlier this year, the sculptor and disability rights activist Tony Heaton held an exhibition of his work at the Attenborough Arts Centre in Leicester featuring pieces that reflected the artist’s own lived experiences as a disabled person.

The show, called Altered, included works made over the past four decades,

and highlighted Heaton’s experience of disability in an ableist world. It encapsulated his subversive approach through pieces “altered” or changed in some way, such as the playful neon piece titled Raspberry Ripple (2019).

“For disabled people, it’s rhyming slang for cripple… it’s kind of an in-joke, there’s layers to the work,” he said in an accompanying film. But the "p" was missing from the word "raspberry" in Heaton’s neon piece.

“You dispense one of the p’s and nobody notices. We often talk about the deficit model of disability, as if you are perceived to have something missing or being lesser.”

The disability art movement began in the 1980s to address the under-representation of disabled artists in UK public collections and also accessibility issues.

Heaton was one of those who helped change perceptions during his time as director of Holton Lee in Dorset, a 350-acre campus with short-stay residential facilities for disabled people.

“I set up the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive (NDACA) there and started collecting works of disabled artists who exhibited with us,” Heaton said in a discussion with gallerist Jennifer Gilbert in 2020.

“I wanted all the art on the walls to be by disabled artists. I wanted to give a subversive message that disabled people were creative and made brilliant work.”

The NDACA, which Heaton created with project director David Hevey, is now run by disability-led arts organisation Shape Arts, which Hevey heads. The archive includes 3,500 images, oral history film interviews and educational resources.

“The problem comes when non-disabled people put barriers in the way: steps, no dropped kerbs and so on,” says Heaton. “The world is built for people like you rather than people like me. A lot of my work speaks about that.”

Heaton emphasises the importance of the social model of disability, which underlines that people are disabled by barriers in society.

“You need to understand the social model of disability as a fundamental emancipatory tool – it helps us to understand disability as a social construct and it helps us to identify barriers to inclusion,” he says.

Other activist artists are also prompting disabled and non-disabled people to rethink their biases and preconceived notions of disability and ableism (discrimination in favour of able-bodied people). The Leicester-based artist Christopher Samuel makes work about identity and disability politics.

A range of his work could be seen earlier this year at the Attenborough Arts Centre in the exhibition, Christopher Samuel: The Archive of An Unseen.

The show explored the artist’s experiences growing up as a Black, disabled, working class child from a single parent home in the 1980s and 1990s.

“The aesthetic of my work matters,” he says, referring to a 2019 work called Welcome Inn, an “inaccessible” hotel room in a functioning hotel called the Art B&B in Blackpool.

“I want my work to be beautiful or playful and to draw people in, even if there is something darker beneath the surface. I like the play between these things.”

This year, Samuel also contributed to a research project between the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries at the University of Leicester and the National Trust called Everywhere and Nowhere, which explored untold histories of disability from across the trust’s sites and collections.

His work is politically charged and though he does not consider himself an activist, he sees the value in activism.

“Disabled activists are important because they are beacons for other disabled people to see the possibilities of fighting for more, and giving them the courage to speak up when something isn’t right,” Samuel says.

“Activists show us it is ok to go against the grain and to fight the social preconceptions and accepted norms that exist about disabled people. We all have unconscious biases, and sometimes it takes people like activists to make us aware of that and to engage with making changes.”

Shropshire-based artist and consultant Zoe Partington uses her art to challenge difference and open up discourse about the experiences of disabled people.

“I make folks unpick their bias and recentre their own experiences to engender change,” Partington says. “In many ways I have put the activist and speaking up about the value of thinking differently before my own practice and access needs.

“It’s hard work – you have to be well informed and recognise ‘ableist’ approaches and how these manifest in various forms. I have to constantly challenge the myths and negative notions of the medical model and ‘impairment focus’.”

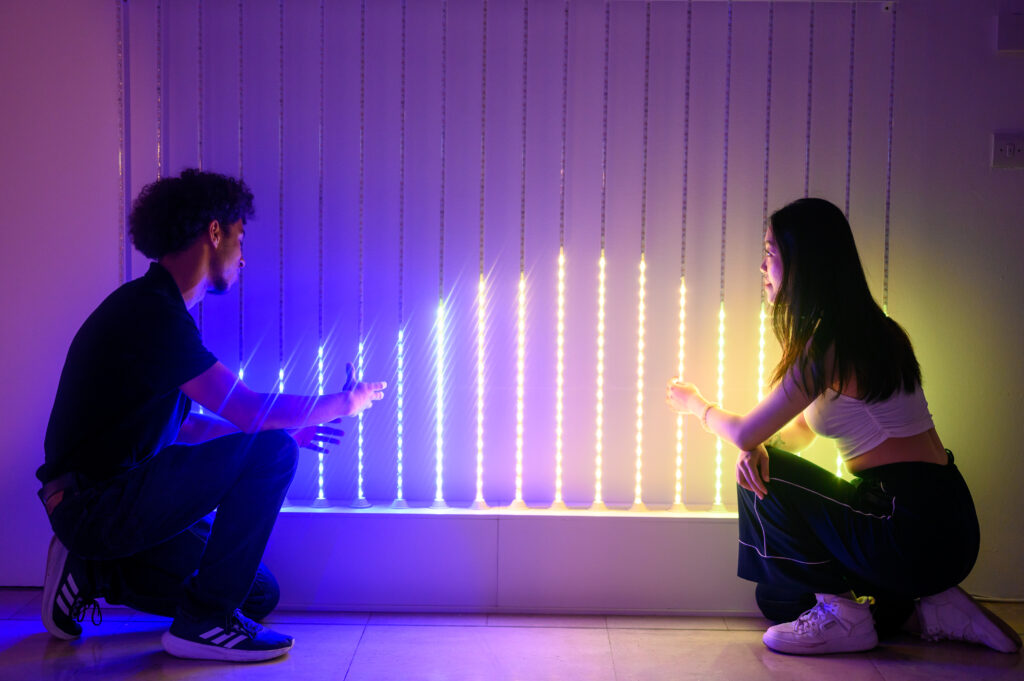

This year, Partington devised Decoding Difference in collaboration with King’s College London. The work, shown as part of the London Design Biennale in June at Somerset House, prompted viewers to look at a moving light installation based on the artist’s blood glucose levels, investigating the objectification of disabled people and their personal lives.

“All my work embeds another layer and often I like to subvert the art by providing access for sighted audiences as the add-on instead of providing audio description as the add-on,” Partington says. “In my work, the audio description and sound may be the starting point, not the visual part.”

Creative touch

Artist Clarke Reynolds had a solo exhibition titled The Power of Touch at Quantus Gallery in London earlier this year. Visitors were asked to wear special glasses that enabled them to sample Reynolds' braille art in “much the same way a blind/partially sighted person would”, the gallery said.

“Seeing without seeing is a tagline that describes my art,” Reynolds says. “Not only can you see the art but you can touch it as well, making it accessible to visually impaired people.

“I hate the word disability – we’re not disabled – society makes us that,” Reynolds continues. “It’s a very political word. I’m blind but I’m not disabled and that’s key. I wear blindness as a badge of honour. I was an artist before I lost my sight. Because I lost my sight, society deems it to be a hobby.”

Reynolds recently received funding from Arts Council England to research audio-description guides for visually impaired visitors. For him, most guides in museums and galleries are inadequate.

“These guides are so boring,” he says. “Look at audio books and how enticing they are. Audio description should involve someone excited telling you an engrossing story. I want to be able to experience the art just as you experience it, for the emotion.”

A key issue is the need for museums to work ethically and inclusively with disabled artists. As many museums are publicly funded, it is clear disabled people should have an equal stake in these organisations.

And that disability inclusion, and diversity of representation in general, should be built into the structure of such institutions.

A number of organisations are fighting for change in the sector, including Unlimited, which recently asked disabled artists, arts workers and creatives about their experiences of working in the sector.

The survey, which attracted more than 300 responses, found that 87% of those participants had been asked to do something for nothing.

In response, Unlimited has been asking organisations to pledge to help change the culture of exploitation within the cultural sector, particularly towards disabled artists and creatives.

Many arts organisations are aware that they need to do more to support disabled artists, whether that is related to collections, access or recruitment.

“There is a lot more work to be done in drawing out histories of disability within our existing collection and finding new ways to make those stories visible to our audiences,” says Helen O’Malley, curator of community programmes at Tate Modern, London.

“After all, so many great artists, from Henri Matisse to Frida Kahlo, made work while living with disabilities.”

Tate was involved in a project called We Are Invisible We Are Visible, which took place last year and was funded by the Ampersand Foundation.

This was organised by the disabled-led visual arts organisation Dash and involved 31 disabled and neurodivergent artists creating events at the 30 venues across the UK that are part of the Plus Tate network, which supports the development of the visual arts.

Art and activism

Members of the network, which includes Tate’s four sites, hosted interventions that saw artists respond to the First Dada International Exhibition, which was held in 1920 in Berlin.

Dada was an art movement formed in response to the horrors and folly of the first world war, and the aim of last year’s event was to channel the defiant and absurdist spirit of the movement, purposefully provoking visitors to reflect on the societal barriers that continue to restrict and exclude disabled people today.

Barriers to access and inclusion are key issues for the arts community in Wales. Its aims are set out in the Widening Engagement Action Plan 2022-25, including recommendations on how to improve engagement with communities that the arts sector has consistently failed to engage with.

The report states: “Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales and the Arts Council of Wales believe that culture in Wales should reflect the lives of all its citizens.

“People who are culturally and ethnically diverse, neurodivergent, D/deaf and disabled people, and people facing social-economic disadvantage, not least those in post-industrial communities, are integral and central to our cultural life. These histories are Wales’s histories, and our two organisations will do everything to ensure they are at the centre of cultural practice in Wales.”

Amanda Wells, a disability writer and artist based in North Powys, wrote an interesting blog on the Amgueddfa Cymru website that set out some of the key challenges and aspirations going forward.

“Through persistent effort, disabled and disability artists have got a foot in the door of the major institutions,” Wells wrote.

“Networks such as Disability Arts Cymru and Disability Arts Online support, encourage and inform disability artists. There is a growing sense of self-belief among disability artists that our work is important, significant, aesthetic and every bit as deserving of gallery space as any other work.

She added: “There is some progress in the opening up of the mainstream art world for disability artists. Disability artists are passionate about and committed to their work, and this will carry us forward… until there is a truly inclusive art world.

“There is a long way to go, and it will take a great deal of determination, but disabled people are used to having to be determined just to navigate everyday life, so I am sure that as artists we will continue to apply pressure and force that door open wide.”

Gareth Harris is a freelance arts writer. Artists Christopher Samuel and Tony Heaton are speaking at this year’s Museums Association Conference in Newcastle-Gateshead